Sagarmanthan: The Great Ocean Dialogue (Prelims & Mains- Polity & Governance)

Why in news?

Sagarmanthan Draws Successful Closure with Focus on Applying Knowledge for Sustainable Evolution of Maritime Sector.

India’s maritime tradition goes back several millennia and is among the richest in the world. The thriving port cities of Lothal and Dholavira, the fleets of the Chola dynasty, the exploits of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj are great inspirations.

About Sagarmanthan:

Sagarmanthan – The Great Oceans Dialogue, an initiative by the Ministry of Ports, Shipping & Waterways (MoPSW) and the Observer Research Foundation (ORF).

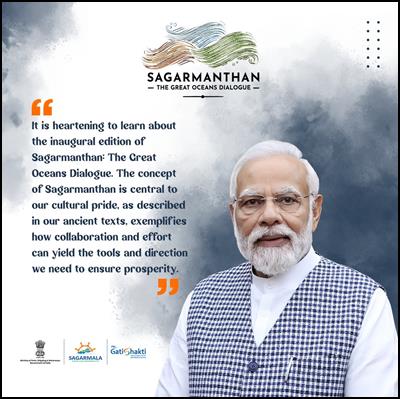

Sagarmanthan is designed to facilitate in-depth discussions on key aspects of the blue economy and maritime governance. Its structure revolves around four interconnected themes, each addressing critical challenges and opportunities shaping the future of the oceans.

Four central themes are:

India’s maritime legacy is as vast and dynamic as its 7,500-kilometer coastline, which anchors 12 major ports and over 200 minor ones. Positioned along the world’s busiest shipping routes, India is not just a key trading hub but a rising global power.

To lead in global maritime governance, India must foster deeper engagement with policymakers, business leaders, and thought leaders. By shaping conversations around sustainable practices and forward-thinking strategies, India can redefine its role in the maritime domain.

Sagarmanthan offers a premier platform for global leaders, policymakers, and visionaries to share insights and shape the future of the marine sector. With critical themes spanning the blue economy, global supply chains, maritime logistics, and sustainable growth, the dialogue aims to chart a bold, actionable course for a vibrant and future-ready maritime ecosystem.

The Indian Government has played a crucial role in fostering growth. Policies such as allowing 100% Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) under the automatic route for port and harbour projects and offering a 10-year tax holiday to enterprises engaged in port development have bolstered the sector. These measures, combined with the nation’s expanding trade networks, position India’s maritime industry as a cornerstone of its economic ambitions.

Some of the major recent developments and initiatives:

- In 2023-24, major Indian ports reduced container turnaround time to 22.57 hours, exceeding global benchmarks. Paradip Port earned ₹1,570 crore (US$ 188 million) with a 21% rise in net surplus, while Jawaharlal Nehru Port reported a net surplus of ₹1,263.94 crore (US$ 151 million).

- Paradip Port became India’s largest major port by cargo volume in FY24, handling 145.38 million tonnes. It surpassed Deendayal Port Authority due to enhanced operational efficiency, record coastal shipping traffic, and a surge in thermal coal shipments.

- India has outlined investments of US$ 82 billion in port infrastructure projects by 2035 to bolster the maritime sector.

- The ‘Panch Karma Sankalp,’ announced in May 2024, includes five major announcements focusing on green shipping and digitization: MoPSW will provide 30% financial support for promoting Green Shipping;

- Under the Green Tug Transition Programme, Jawaharlal Nehru Port, VO Chidambaranar Port, Paradip Port, and Deendayal Port will procure two green tugs each;

- Deendayal Port and VO Chidambaranar Port, Tuticorin will be developed as Green Hydrogen Hubs.

- A Single Window Portal will be established to facilitate and monitor river and sea cruises; and Jawaharlal Nehru Port and VO Chidambaranar Port, Tuticorin will be transformed into smart ports by next year.

Government Schemes in the Maritime Sector

The Indian maritime sector plays a critical role in supporting the country’s trade and economic growth. Several government schemes have been launched to modernize infrastructure, enhance port connectivity, and promote sustainability in the sector. These initiatives aim to strengthen India’s position as a global maritime hub and improve its efficiency across various maritime segments. Here are some of the major schemes in the maritime sector:

- Sagarmala Programme

- Maritime India Vision (MIV) 2030

- Inland Waterways Development

- Green Tug Transition Program (GTTP)

Conclusion:

By enhancing port efficiency, reducing turnaround times and strengthening last-mile connectivity through expressways, railways and riverine networks, we have transformed India’s shoreline.

Today, the security and prosperity of nations is intimately connected to oceans, and recognising the potential of oceans, several transformative steps have been taken to bolster India’s maritime capabilities.

How India Can Counter the CBAM (Prelims & Mains- Environment)

Why in news?

The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (EU-CBAM), the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, and the EU Deforestation Regulation, have led to concerns in developing nations. India has criticised the EU-CBAM, in particular, as being “arbitrary”.

About the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

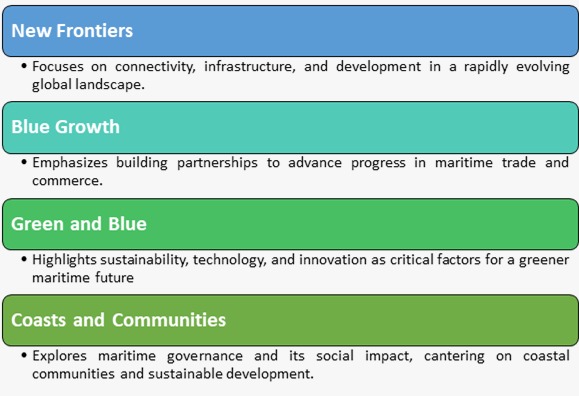

- The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is the EU’s tool to put a fair price on the carbon emitted during the production of carbon-intensive goods that are entering the EU, and to encourage cleaner industrial production in non-EU countries.

- By confirming that a price has been paid for the embedded carbon emissions generated in the production of certain goods imported into the EU, the CBAM will ensure the carbon price of imports is equivalent to the carbon price of domestic production, and that the EU’s climate objectives are not undermined.

- It is designed to be compatible with WTO rules.

- CBAM will apply in its definitive regime from 2026, while the current transitional phase lasts between 2023 and 2025. This gradual introduction of the CBAM is aligned with the phase-out of the allocation of free allowances under the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) to support the decarbonisation of EU industry.

Impact of CABM on India

The CBAM is meant to ensure that imported products bear a carbon emission cost comparable to the cost imposed on goods produced within the EU. Exporters will be mandated to provide information on the quantity and emissions of their goods and buy certificates to match those emissions.

- The EU comprises 20.33% of India’s total merchandise exports, of which 25.7% are affected by CBAM. During the last five fiscal years, iron and steel have accounted for 76.83% of these exports, followed by aluminium, cement, and fertilisers.

- Developing countries argue that such measures might contravene international climate agreements that prevent one country from imposing emission reduction demands on others.

- The proportion of coal-fired power in India is much higher than the EU and the global average.

- CBAM poses challenges to those industries that are exporting to European markets in terms of increased compliance costs such as the requirement to monitor, calculate, report, and verify emissions.

The current production-based accounting principle practised under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) includes the emissions resulting from the production of exportable commodities within the emission inventory of the exporting nation. The exporting nation is held accountable for the reduction of these emissions, even though these products are not consumed within its domestic market.

As a result, many developing economies (like India) with less stringent emission reduction measures are accused of climate change when they export more.

Arguments Raised by India

India’s arguments should also align with other developing countries’ agenda, if India wishes to speak like a leader.

1. Time for preparing for CABM: With administrative deftness, the EU set a target to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 20% compared to 1990 levels by 2020; this is outlined in the EU Climate Action and Renewable Energy Package in 2008. Following the accomplishment of these targets, the European Green Deal was unveiled in 2019, extending the emission reduction target to 55% below the 1990 levels in a Fit for 55 Package.

Does the CBAM offer developing economies a matchable time to adapt?

2. Empowerment: The EU has decided to keep the revenues generated from the CBAM as its resources, which will be used to fund the NextGenerationEU recovery tool and operate the CBAM. Depending on the mechanism’s ultimate design, the anticipated additional money generated by CBAM for 2030 is estimated to be €5 to €14 billion annually. Sharing this revenue with non-EU trading partners may contribute to capacity building and technology transfer in developing economies.

Is it appropriate for the EU not to share this revenue with non-EU trading partners?

3. Quantifying Emission Reduction Responsibilities: Equity-based Accounting (EBA) of Nationally Determined Contributions, emphasises a collective obligation for emission reductions among trade partners based on the ideas of horizontal intra-generational equity and vertical inter-generational equity. In the context of the EU-CBAM, India can introduce the concept of EBA to the developing world concerning retaliation measures. Using the EBA, a formula can be proposed to calculate the tariff base on imports from the EU, which considers factors such as relative per capita GDP, relative per capita emissions, relative gains from trade, and relative avoided emissions through trade. By expressing the actual emissions embedded in imports in a way that reflects the developmental and historical heterogeneities between trade partners, any developing economy can be better positioned under these new rules of the game, which provide an unbiased evaluation of climate initiatives.

Measures that India can take

India has to develop long-term strategies and take measures in both domestic and international fronts.

Domestic Level: Government schemes like the National Steel Policy and the Production Linked Incentive scheme should be complemented by a decarbonisation principle.

International Level:

- India should negotiate with the EU to transfer clean technologies and financing mechanisms to aid in making India’s production sector more carbon efficient. One way to finance this is to propose to the EU that it set aside a portion of its CBAM revenue to support India’s climate commitments.

- Strengthen India’s emission monitoring and measuring capacity.

- India should also lead the SAARC countries in enhancing their trade among themselves so as to develop an alternative market for their carbon-intensive exports.

The allocation of emission responsibilities is not equitably assigned to countries based on their historical contributions to climate change or their capacity to mitigate its effects. It is apparent that through CBAM, the EU wants to intimidate non-EU nations into adopting its self-proclaimed position as climate leader.