Apes and humans belong to the families Simidae (with the exception of the gibbon, which is classified under the family Hylobatidae) and Hominidae, respectively. Both groups are part of the sub-order Anthropoidea and the order Primates. An understanding of the relationship between apes and humans can be achieved through a critical examination of their various anatomical features.

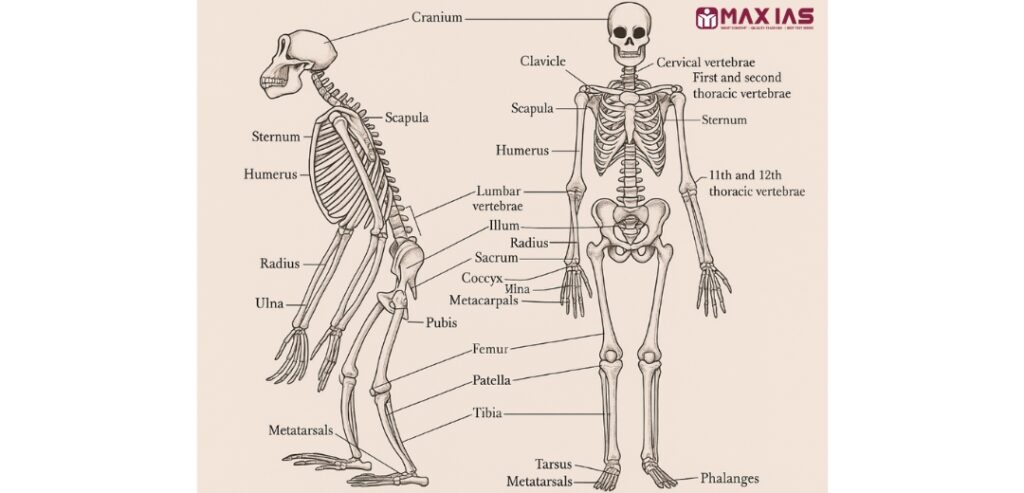

Major bones of the chimpanzee (left) and human (right) skeleton.

The skull

The skulls of humans and apes exhibit several important differences.

In humans, the frontal area of the skull is highly developed, with the forehead rising almost vertically. The region above the eyes, known as the supra-orbital ridge, is not as pronounced; it may be weak, barely noticeable, or moderately developed.

There is no ridge along the sagittal plane of the skull. The upper jaw (maxilla) and the area in front of it (pre-maxilla) are fused together.

The foramen magnum, a large opening at the base of the skull, is positioned centrally. This results in a well-balanced head and a vertical face. Additionally, the muscle attachment line at the back of the skull is located lower down.

In contrast, in apes, the forehead is less developed, and the head slopes backward. The supra-orbital torus is prominent and well-developed, and a ridge runs across the top of the skull. Unlike in humans, the maxilla and pre-maxilla are separate. The foramen magnum is situated further back at the base of the skull, causing the ape’s face to hang downward. The muscle attachment line at the back of the skull is positioned higher up.

The lower jaw

The lower jaw of humans is relatively small when compared to that of apes. The muscle responsible for moving the lower jaw in humans is weak. Notably, humans typically possess a well-defined chin, and their facial structure does not project forward; however, some rare instances of lower jaw prognathism can occur. In contrast, the lower jaw of apes is massive and lacks any semblance of a chin. Their muscles for jaw movement are strong and well-developed, and facial prognathism is quite common among apes.

The morphological differences between humans and apes are significant, particularly when examining dental structures, nasal morphology, lip configuration, limb adaptations, femoral characteristics, and overall body dimensions.

Dental structure

In humans, the dentition is characterized by smaller tooth size compared to that of apes. The canines do not exhibit pronounced protrusion beyond the occlusal plane of the adjacent teeth. Human mastication involves a dual movement pattern, encompassing both lateral and vertical motions, commonly referred to as rotary motion. The dental arch in humans is parabolic in shape, in contrast to the U-shaped dental arch observed in apes. The dentition of apes, with larger teeth and canines that project beyond the level of surrounding teeth, facilitates interlocking when the jaws are closed, thereby restricting lateral chewing motion. Consequently, the mastication in apes primarily consists of a vertical grinding action.

The nasal structure

From an anatomical perspective, the nasal structure in primates consists of two parallel bony plates connected by a suture along the midline. Extending from these nasal bones, the cartilaginous structure divides into two separate nostrils, bisected by the septum. The human nose is notably well-developed, featuring a subtly elevated root and bridge, with the cartilaginous portion prominently projecting above the facial surface. The bulbous tip of the human nose extends over the septum, and the nostrils are smaller and generally oriented downward. In contrast, the nasal morphology of apes lacks significant elevation at the root and bridge, with a pronounced width and little prominence of the cartilaginous portion. The absence of a well-defined tip results in nostrils that appear as large apertures.

Lip configuration

In terms of lip structure, ape lips tend to be stretched over robust jaws, characterized by a thin texture with diminished visibility of the red portion when the mouth is closed. The integumental lip possesses minimal adipose tissue. Conversely, the human upper lip features a median furrow extending from the nasal septum to the edge of the membranous lip, a distinctive trait of human anatomy. Human lips exhibit considerable variation in thickness, ranging from thin to very thick.

Limb adaptations

Limb morphology reflects significant behavioral adaptations. The arms of apes are elongated, facilitating a mode of locomotion termed brachiation, as described by Keith. During this locomotor activity, apes utilize a branch to propel themselves upward by flexing their arms, employing a lever mechanism where the shoulder joint serves as the suspension point and the elbow acts as the fulcrum. In contrast, humans engage their arms primarily for weight-lifting, utilizing the elbow joint as a fulcrum and applying power through the forearm, which functions as the movable lever. This results in a reduction of the upper arm length in apes compared to the forearm length observed in humans.

The femur

The femoral structure also demonstrates notable differences: the femur in apes is short, thick, and curved, contributing to a shambling gait, while that of humans is long, slender, and elongated. This disparity is further evidenced by the greater development of muscle attachment ridges in the human femur, particularly the linea aspera, which is associated with the enhanced development of extensor muscles critical for maintaining an erect posture and a bipedal gait. Consequently, the cross-sectional shape of the human femur is prismatic, whereas in apes, it presents a more rounded or oval configuration.

Foot

The anatomy of the foot has undergone considerable evolution in humans, who exhibit a foot structure adapted for bearing body weight and facilitating upright locomotion. In contrast, ape feet are also suited for grasping branches, featuring a non-opposable great toe aligned with the other digits. The lateral toes in apes are notably more developed, while human feet display distinct transverse and anteroposterior arches.

Body dimensions

Regarding body dimensions, ape species show considerable variation. The gibbon is recognized as the smallest ape, averaging a height of 3 feet and a weight of 14 to 18 pounds. The orangutan reaches an average height of 4 feet 6 inches, with a weight of approximately 165 pounds. The chimpanzee and gorilla represent the tallest apes, with average heights of 5 feet and 5 feet 6 inches, respectively, and corresponding average weights of 100 pounds for adult male chimpanzees and 350 to 650 pounds for adult male gorillas. In contrast, the average height of humans is approximately 5 feet 6 inches, with an average weight of 145 pounds.

Vertebral Column

The human vertebral column is distinguished by four alternating curves, which function to support and distribute the weight of the head and trunk in an erect posture, whereas the vertebral column of apes is characterized by only two such curves.

Brain

In the realm of brain development, humans exhibit a significantly higher level of advancement compared to non-human primates, particularly apes. The human brain not only possesses a greater overall mass—averaging three times the weight of a gorilla’s brain, the largest among the apes—but also displays a sophisticated level of development. Notably, the frontal region of the human brain is markedly more advanced, and the cerebral cortex demonstrates a complexity in convolutions that far exceeds that found in apes. It is crucial to acknowledge that while these structural differences are considerable, they are fundamentally differences of degree rather than of kind.